At twenty-three, I was easily the oldest member of a rag tag group of college players from the Northwest spending its spring break barnstorming through Southern California in March of 1989. A fifth-year senior still recovering from a shoulder reconstruction performed less than a year earlier, I was the de-facto elder statesman on a team of talented freshmen and a handful of misfit upperclassmen, like me, who were nearing the end of their playing careers. We’d lost our first four in Los Angeles and after a five-hour drive north from Malibu, I pulled the last of three rented Econolines under the porte-cochere at the Piccadilly Inn, dutifully behind those driven by my coaches. It had been a tough trip, a disappointing start to a season filled — like all seasons — with hope. In our defense, it had not been a patsy schedule — Fullerton, Long Beach State, Pepperdine — but if we were going to salvage a win, we’d now have to do so against the Fresno State Bulldogs, ranked number one in the country at the time and coming off a trip to the College World Series a year earlier. How we tolerated the twelve-hour drive home would be determined by how we fared in the two games we had scheduled against the Bulldogs the next two days.

The Piccadilly Inn was a sprawling hotel property, at least by Fresno standards. Four rectangular buildings, each three stories high, surrounded a courtyard swimming pool and contained nearly two hundred guest rooms and party space that served as a magnet for weddings, corporate meetings, and reunions from around the San Joaquin Valley. It was clean. It was cheap. And it was a ten minute walk to the ballpark.

A few blocks north, just beyond Bulldog Village and across Cedar Avenue from Fresno State University, sits Beiden Field, the baseball diamond named for FSU legend Pete Beiden, who after a short stint in the California League, guided the Bulldogs baseball team from 1948 to 1969. Beiden died at the age of ninety-two in 2000, thirty years after turning over the program to Bob Bennett.

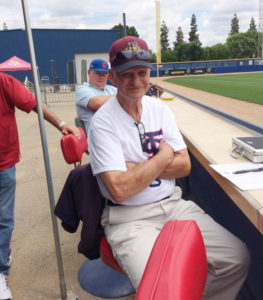

I first met Coach Bennett — which is to say I first saw him — the night we arrived in Fresno. After a quick bite to eat, several of my teammates and I walked to Beiden Field from the Piccadilly to catch the Bulldogs’ game against the University of San Fransisco. The ‘Dogs were manhandling USF while the pastoral coach gazed upon his flock from a folding chair at the far end of the dugout — handsome, quiet, collected, legs crossed and taking notes on a small piece of paper, perhaps the back of a lineup card. Meanwhile, his team performed flawlessly and with the kind of passion and enthusiasm reserved for very good teams that are in the midst of extending a winning streak. While the boys hustled, hollered, and high-fived each other, Coach Bennett sat still, writing frequently, and only occasionally turning his head to say something to third base coach Mike Rupcich.

It’s easy when you’re winning, I thought.

It was a warm evening in mid-March. I was one of more than 3,000 spectators seated in the finest college baseball stadium in America — a mountain of cement terraces anchoring 3,575 red theatre-style chairs that surrounded a manicured playing surface as green and as smooth as a Pebble Beach fairway. When the San Francisco Giants pulled out of their working agreement in 1987, ending Fresno’s 46-year relationship with the California League, the Bulldogs were suddenly the only game in town. An agricultural community with great weather, a beautiful and inviting ballpark, and a top-ranked team: it was the recipe that enabled Fresno State to lead the nation in attendance for the second year in a row.

Playing on the field below me were nineteen Bulldogs who would go on to play professionally, including four first-round draft picks and five future Major Leaguers, among them Bobby Jones, Tom Goodwin, Steve Hosey, and Eddie Zosky. They were remarkable athletes, impressive to watch. But as damaged goods, a misfit player slowly watching my dream of playing Major League Baseball fade away, I was already planning a transition to a coaching career. Therefore, it was not the players, but the architect of the program’s success — Bob Bennett — who held my attention.

He was unusually calm for a coach. Sitting. jotting, moving only enough to recross his legs every inning or so, and standing just twice in nine innings: once to have a quick word with his pitcher in the middle of the dugout, and the other simply to refill his water cup. He showed emotion neither when his team executed perfectly, nor on the rare occasion when his pitcher left one over the plate. He sat at the far end of the dugout where the view to all corners of the field was unobstructed, and where he was safely removed from the emotion that often resides near the bat rack. He did not give signs, pace in front of the bench, or whine and holler at the umpires. My attention was drawn to Coach Bennett by the sheer fact that he drew none to himself.

It was theatre: a play that unfolded on a dirt and grass stage while the director watched patiently from the curtain’s edge, comfortable with the knowledge that he was unable to act in place of his performers once the lights came on, and confident that the demands of his rehearsals would eliminate the need for him to do so. Coach Bennett’s company was better prepared than any team I had ever seen. His actors hit their marks with precision, timed their lines perfectly.

Miraculously, we salvaged our spring trip by unexpectedly beating the best team in the country the next two days. The outcome was so unlikely, in fact, that I predicted it to be the highlight of the ’89 season, merely something that would make the twelve hour drive home a bit more tolerable. I was wrong because ten weeks later we returned to Fresno after my team won its conference tournament and secured an automatic bid to the NCAA tournament — the “Road to Omaha.” Unfortunately for us, the road was short — little more than a driveway, really — and came to an abrupt end after consecutive losses to Wichita State and Notre Dame at the Western Regionals. I played my last college game at Beiden Field.

The Pepsi-Johnny Quik Tournament, a hallmark of Coach Bennett’s brilliant career at Fresno State, was once regarded as the best pre-season college baseball tournament in America. Eight teams from all over the nation descended on Beiden Field each March for six days of baseball hosted by Fresno State and the Bulldog Dugout Club, a fiercely loyal group of volunteers that proudly supported college baseball and especially their own Bulldogs players and coaches. In 1999, ten years after my college playing career ended at Beiden Field in an eleven-inning loss to Notre Dame, I returned to Fresno to coach a team that was participating in the PJQ. Following a three-hour drive from the Sacramento airport, a charter bus delivered us to the Piccadilly on a warm spring day in the Valley. Waiting there for us under the porte-cochere were Bill and Lori De Luca, our Dugout Club team hosts, and their young daughter, Melissa. Together, they welcomed us to town and showered our players with fresh fruit from the Valley, cold drinks, homemade cookies, and gift bags that included tournament t-shirts and more snacks. Bill, wearing bluejeans and a Fresno State baseball cap and t-shirt, handed me the keys to a new SUV and said it was for my use while we were in town, even though everything we might need — food, shopping, even the ballpark — was within walking distance. “But,” Lori said, “if there’s anything your team needs, please just let one of us know so we can take care of it. Focus on your games, Coach. By the way, we’d like to provide a hot lunch for the team right after Wednesday’s 10 AM game, if that’s okay. Melissa here has been busy baking cookies for the boys; we’ll meet the them right outside the ballpark after each game — win or lose — with snacks and cold drinks.” “Oh,” said Bill, “and we’d sure like it if your coaching staff could spend as much time as possible in our private Dugout Club area on the third base line … you know, when your team’s not playing. We’ll have all the food and beer there you could possibly want. W’all just like getting to know you while you’re in town, that’s all. We want you to have a great time and come back next year, you know?”

The unexpected meeting with the De Luca family caught me by surprise because it ran counter to my experience as a young Division I head coach. In a flash, I recalled host teams that routinely did not supply a game ball for my starting pitcher; bullpen mounds that were purposely left in disrepair; having the BP ball basket removed from the mound, leaving me to throw forty minutes of batting practice while bending to the ground each time I needed baseballs; and having portable speakers the size of Fiats curiously positioned inside our dugout, blaring death metal so loudly Ted Nugent would have been diving for a bunker. But while the average college team found ways I considered disrespectful and childish to make their opponents miserable, even before the game started, Fresno State had sent the De Lucas bearing gifts. Was this for real, I wondered.

Sheepishly, I offered Bill, Lori, and Melissa caps and t-shirts bearing my team’s logo. “Oh, that is great!” said Lori. “Yeah,” Bill added, “we’ll wear them for all your games this week. Except, of course, when you play Fresno State.” Leaning in, he added, “We wear our team colors then. Hope you understand.”

Later that night, Bill and Lori escorted my assistant coach and me to campus for the tournament banquet, a kickoff affair attended by excited Dugout Club members and FSU Bulldogs fans. Each coach was asked to say a few words about his team. Coach Bennett, classically dressed in a brown sport coat and tie, regaled a wonting crowd with inside information about the development of his club during the first four weeks of the young season. After that, he read poetry — his own. Four days later his team beat the hell out of us.

In the Dugout Club, food was offered no matter what time I strolled through the gate: pancakes, sausage and eggs in the morning; sandwiches, burgers and wraps at lunch; a hot dog anytime you wanted one. Dinner was catered by local restaurants and awaited eagerly by the men and women who mingled between the wooden snack shack and the fence line barstools my friend John Longstaff calls the Rail. Cigar smoke, generally of good quality, filled the air and mixed easily with the laughter and conversation enjoyed by the Railbirds and the other unpretentious, hard-working, good-hearted people of Fresno, who just happened to be savvy, educated baseball fans. They loved their Bulldogs players and the men who coached them — hard-nosed and gritty Steve Pearce, loyal and gentlemanly Mike Rupcich, and of course Bob Bennett — more than anything. A close second, however, was the opportunity to get to know the kids and coaches who traveled to Fresno each year for the Pepsi-Johnny Quik Classic.

When I returned to the PJQ in 2001, I brought with me a scrappy group of dirt dogs that found ways to win. By winning our first four games of the tournament, we set up a Friday night showdown with Fresno State to determine who would play Notre Dame in Saturday night’s championship. Around nine that morning, I was rousted from my bed when my roommate and lone assistant coach, Ryan Brust, screamed an obscenity from the bathroom. An instant later, I heard a crash of such prolific force and commotion, I thought the Russians had detonated Tsar Bomba. Unsure what had just happened, I immediately sprinted to the bathroom where I found Ryan lying naked in the bottom of the tub. He was contorted in an old-fashioned hook slide position, with one leg tucked beneath his rear end, the other extended in a cramp against the toilet. The shower curtain, which he’d clung to in an effort to save himself, as well as the tension bar from which it hung, was now resting across his head and chest, concealing neither his naked body nor the steady stream of curse words he spat from the tub floor. I like to think I confirmed the absence of serious injury before my sides began to split, but I’m not sure that was the case. For the next three hours I laughed uncontrollably.

By noon, we’d collected ourselves and made our way over to the Dugout Club to watch the end of the Navy-Bucknell game when Coach Bennett walked through the open gate and pulled up a chair at our table. I was still a young coach — 36 at the time — and greatly admired Coach Bennett, who was nearing 70 and approaching 1,300 wins at Fresno State. The man had built a dynasty at FSU, realized his dream of constructing a spectacular stadium, and inspired the Dugout Club in which we sat. He’d done everything I wanted to do as a coach and I was in awe of him. Needless to say, having him approach our table was a great thrill.

I thought he’d say hello, stiffly, then be on his way. But I had miscalculated the heart and soul of Bob Bennett. We talked for an hour before he invited Ryan and me into his office to escape the midday Fresno sun. Eventually, the subject turned to bunt defense. Just hours before our teams would square off in a game to determine which of us would play in the championship against Notre Dame, Coach Bennett was drawing bunt plays and rotations on napkins in his office. Not that one team’s bunt defense is necessarily much different than another’s, but sharing like this is rare in sports. Football and basketball coaches tend to guard their information strictly — I’m not sure Bill Belichik or Chip Kelly would ever open their play books to me, and certainly not to each other — but Coach Bennett was sharing his expertise with someone he barely knew, mapping out a part of his game plan and asking nothing in return.

Eight hours later, I was ejected from the game following a close play at the plate, banished to the barren visitors clubhouse, and forced to get play-by-play updates from Zach Yarbrough, an off-duty pitcher. In a hard-fought battle, and on the backs of Eric Hull, who pitched a complete game, and Brock Griffin, who delivered a two-run double to put us ahead for good, my team came out on top.

Neither team attempted a single bunt.

Three years retired and adjusting well to a Parkinson’s diagnosis, Coach Bennett took my call in June of 2005. Could I come visit in order to learn more about coaching pitchers, I asked. We did not know each other well and I was nervous to make the call. Aside from trading lineups at home plate on two trips to the PJQ, the only real conversation I ever had with the man was the day he shared his bunt defense with me, which was, of course, what I remembered when I thought to call in the first place. “Chris,” he said, “I’ve been doing this for more than forty years. You can have everything I’ve got. Come on down. We’ll meet here in my den.”

I flew to Fresno three weeks later, arriving at the small Fresno airport around 9 AM. Coach Bennett met me at the security checkpoint, insisted on taking my bag and my briefcase from my hands, and led me to his white pickup, a retirement gift from the Dugout Club. We drove to his home where we met Bob’s wife, Jane, before heading to his den to talk baseball. For two days, one subject led to another, and then another, and ultimately to the file cabinets from which he pulled reams of information, not just about the pitching I had come for, but about coaching all areas of the game, and the many facets of running a successful baseball program. We broke only for dinner at the Spaghetti Factory with Jane and Jeff Prieto, the Bennett’s grandson, who played for Bob at Fresno State before embarking on his own coaching career.

In two days spent holed up in his den, Coach Bennett gave me his whole program — pitching, catching, hitting, infield, outfield, base running, recruiting, discipline, and even the amazing story of how his dream of building the best college baseball stadium in American became a reality when his friend and local businessman Earl Smittcamp took him to see the largest orchardist in the valley.

“I knew that Earl believed in the stadium project,” Bob told me in 2005. “But I didn’t know the man he was taking me to see. I stayed up all night wondering if I should ask him to buy two seat options or four. When Earl introduced us, the orchardist said, ‘Coach Bennett, I don’t know you, but I knew Pete Beiden. He was a good man. And I know Earl here, and he’s a good man. So, you must be a good man. Tell me, Coach, how can I help you today?’ I was about to ask him for four seat options when Smittcamp cut me off. He said to the orchardist, ‘I’m writing a $50,000 check to the project today and I’m going to write another one in six months. We’d like you to do the same.’ Without hesitation the orchardist said, ‘Fine. Is there anything else I can do for you?’ I couldn’t believe it! I would have felt great selling the man a couple of seat options for two grand. But thanks to Earl Smittcamp, I walked out with $200,000. That’s how it all started.”

Beyond baseball and the dynasty he built in 33 years as the head coach at Fresno State, Bob Bennett unknowingly shared a glimpse into his life as a family man, friend, writer, and poet. It was important to him that Jane and Jeff be with us at dinner and that we discussed what was going on in their lives. We stayed in touch by phone and email for several years and occasionally connected at the ABCA convention, but I regret to say we lost touch at a time when the achievements I had hoped to copy were slipping from my grasp. He’s a great coach, I recall thinking that night at the Spaghetti Factory, but an even better man.

“Tip your cap, Blue!” a single voice boomed from the stadium, high above third base. I had just jogged from the visitors’ dugout on the first base side to the third base coaches box where I was watching the Fresno State pitcher throw his warmup pitches. It was my third trip to the PJQ and I had grown fond of the Bulldogs fans. To some extent, I knew what to expect from them.

“Hey, Blue, tip your cap!” came the voice, as big and as baritone as a voice can get.

No response.

A moment later it came again, this time chopped up into staccato blasts. “Third. Base. Blue. Tip your cap!” I glanced at the umpire behind me who stared like a Buckingham Palace guard at home plate before turning toward the outfield in an effort to disappear from view, a tactic that I knew would only stir the fire burning in the stadium.

The booming voice, a lone tuba in a brass band of horns much higher in pitch, belonged to Don Kostrub, a master tailgaiter and arguably the most clever and ardent fan the sports world has ever known. Kostrub, best known by his nom de guerre, Sugar Bear, is a mountain of a man whose height and stature match the voice for which he is Fresno-famous. Over the years he has cultivated a following of loyal minions who harmonize with him from their nearby seats. Together, they provide an element of fan involvement that is witty, wry, coordinated, smart, baseball-savvy, and resides well above the buffoonery that can be heard in most ballparks across the country. For example, each time Bulldogs second baseman Erik Wetzel was announced, Sugar Bear followed with his own introduction: “Now batting … second baseman …Eric …,” then in perfect Snow White cadence, “Wet-zel-while-you-work.” On queue, the rest of Sugar Bear’s section whistled the next bar of Disney’s iconic tune. Clever. Brilliant. And stratospherically above the comments slung by the average fan who believes his ticket price affords him the right to be caustic and profane. Use foul language in Sugar Bear’s section and you will be chastised, publicly, by the big man with the deep voice. Many ballparks, including those at some faith-based institutions around the country, are sparsely filled with parents who sit quietly until their son’s turn at-bat, and with a generation of students who believe fandom requires belittling the opponent with crude, often personal attacks intended to humiliate. In those parks, league-mandated pre-game public address announcements espousing the virtue of good sportsmanship are laughable. At Beiden Field such announcements are simply unnecessary: cross a line of good taste there and you’ll pay the Bear.

Don’t misunderstand: a visiting third baseman who drops a pop-up below Sugar Bear’s seat, will be heckled — mercilessly — just as I was in the third base coaches box during my first visit to the PJQ when, much like the the umpire, I refused Sugar Bear’s demand to “Tip your cap, Three!” Stare elsewhere all you want, I learned, there is no place to hide at Beiden Field. Eventually, I acquiesced to Sugar Bear, a decision that, much to my surprise, was met with enthusiastic applause and a subsequent invitation to the post-game tailgate. Tipping your cap, as it were, was simply the respectful way to return Sugar Bear’s hello, and acknowledgment that you best bring your A-game because you were being watched. Sugar Bear and Inman Perkins, then a 50-something clad in Bulldog red polyester and leading cheers from atop both dugouts (Bulldogs fans fill both sides of the stadium), and the rest of the Bulldogs’ loyal fans were a game factor that could not be ignored. From the first pitch, they breathed as one, working to get inside your head and causing you to error in ways that gave their Bulldogs the upper hand. Play well and Inman would likely be outside the stadium waiting to shake your hand. Sugar Bear? Well, he gives Bear hugs. Big ones, as I found out.

By all appearances, the mayor of the Bulldog Dugout Club was John Longstaff, a former college player at the University of the Pacific who latched onto Fresno State baseball in 1991, seven years after he began managing money in town. A DC Lifetime Member since 1994, John is bright and articulate, humble and refreshingly self-deprecating, possesses a fresh sense of humor and an uncanny ability to welcome an outsider into the fold. Like Bill and Lori De Luca, John pulled me into the Dugout Club each time my team played in Fresno, always making me feel welcome, even special. The day we met, I needed only mention my fascination with the quality and construction of Beiden Field before John insisted on carting me around to show me the other fine local high school and junior college fields in the area. When I flew to Fresno to attend Coach Bennett’s retirement celebration in 2002, it was John who invited me to stay at his home. We have remained in touch ever since.

The Dugout Club is stocked with wonderful people, including Sharlene Gomes, a DC officer who later would think to invite me to Coach Bennett’s retirement party; Marty Mamigonian, who served as the PJQ tournament director; and Larry Buss, who along with his wife, Joyce, once hosted my team, and who generously took my pitching coach and me golfing, beating me so badly I swore the game off for a year.

In Fresno I found that which my wife encourages our children and me to seek out in our daily lives: people who make us better, cause us to want to live a good life, to strive for excellence, to be supportive of others in good times and bad, and to share themselves in uncommon ways. People like the De Lucas and the Longstaffs and the Busses; like Sugar Bear and Inman Perkins; and like the coach who was responsible for all of it. Bob Bennett was inducted into the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame in 2010, but his 1,302 victories at Fresno State, impressive though they may be, are not the reason I admire him. That sentiment is owed to the fact that Coach Bennett let me have a glimpse into his life as a loving husband to Jane and as a mentor to his grandson; it is owed to the relationships that he cultivated with others who shared his passion, ultimately resulting in the formation of the Bulldog Dugout Club and a stadium that began with little more than a dream; and it is owed to the fact that once Bob Bennett reached the top, he was willing to send the elevator back down for someone like me.

I wish I were able to reciprocate the gifts I received from Coach Bennett and my friends in Fresno, but in that way our relationship has always felt unbalanced, tilted in favor of the favorite uncle who simply has more to give to a child. I hope they know that baseball at Fresno State was coached and played the way it was supposed to be; that Bulldogs fans are the best I’ve ever seen; and that making friends with a Dugout Club member is to make a friend with someone you will not soon forget.

Chris Sperry, Baseball/Life

Great story Chris………….. You could be a writer too!!

Chris – another great piece of writing. I too greatly admire Coach Bob Bennett. He and I have had a casual relationship over many years of visiting at the ABCA. We first met in New Orleans, my first ABCA convention. The next year I saw him in the hallway and he waved. I couldn’t believe this storied man could remember this insignificant high school coach. I’m sure the name was nowhere in his consciousness, but recognition just the same. As the years passed we chatted often and he always gave me a bad time about wearing shorts when we were in winter climates in Chicago, Philly, Nashville, or where ever. He is the one guy I really look for when I attend the ABCA each year. We always chat about my former player and friend, Chris Sperry and he shares incidents that he and you experienced. Baseball is blessed with great, sharing people. I feel blessed with the true gentlemen I have met at the ABCA or somewhere in the baseball world over the years; Bob Bennett, John Scolinas, John Winken, Jerry Kendall, Danny Litwhiler, Bobo Brayton, Tim Corbin, and countless others. Yes Chris, we have both been blessed with our involvement in this grand ol’ game. Thank for sharing. All the best to your family.

Thanks, Coach. Look forward to your return.