Originally published in Portland, the University of Portland’s Alumni magazine.

THE JOYS AND TRAVAILS OF BEING A “MAJOR MINOR LEAGUER”

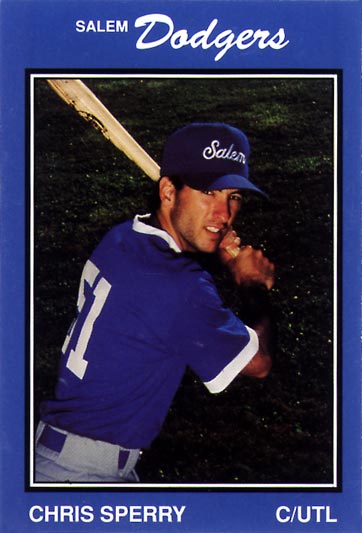

By Chris Sperry ’89

ONE DAY YEARS AGO I SAT IN HANK JONES’S KITCHEN. Hank was a scout for the Los Angeles Dodgers. He had known me since I was fifteen years old, helped develop me as a player, watched me grow through high school and college ball, and was now offering me a chance to play professionally in the Dodgers organization.

My contract lay beneath his fingers. He slid it toward me — then immediately pulled it back out of my reach. Staring me hard in the eyes, he said, “I want you to know something: you will never play in the Major Leagues. But you might manage there someday. I’d like you to do that for us.”

Manage?

Sure, sure — someday, I thought. But not until I proved Hank and every other naysayer, including my parents, wrong.

A LITTLE LATER, I FOLLOWED HANK’S CAR TO SALEM, OREGON, where I would join the Dodgers’ Northwest League team. Alone in my car, I vowed to prove Hank wrong. I had been an underdog plenty before.

When we arrived at the ballpark, it was clear I was indeed a long ways from Dodger Stadium. The field was a well-worn patch of dirt and grass that gave the impression the game should be finished quickly, before the cows returned to feed. The lighting was dim, at best, and the locker room was small and dirty.

The first person I met when I walked in the locker room was Burt Hooton. A big, slow-talking Texan, Burt had just finished a distinguished Major League pitching career (151 wins) and was beginning his first assignment as a minor league pitching coach. I remembered his devastating knuckle-curve; Dodger fans remember him surrendering one of three consecutive titanic home runs by Reggie Jackson in the clinching game of the 1977 World Series. We shook hands. He seemed friendly enough, probably because I didn’t mention Reggie.

Next, I met Tom Byers, the manager, who seemed busy and was immediately on his way to something, or someone, else.

Trainer Geoff Clark issued my uniforms and I began dressing for batting practice. A Dominican player in front of the locker next to me said something to me in Spanish I did not understand. Later I learned there were eight other players who spoke no English. The child of Greek and Albanian immigrants, all I knew in another language was Ti kanis? (Greek for How are you?) and ade sto Diablo, which my Greek grandfather would holler when he was weary of pulling the cord on the lawnmower that wouldn’t start.

I smiled, said nothing, and continued dressing.

By the time the team assembled for stretching, the manager had forgotten my name. He covered by asking me to introduce myself to the team, which I did to 24 other players, most of whom had been together for at least a year, and probably saw me — just as they would any newcomer — as a threat to their job. I immediately felt like an outsider, the new kid at school searching for a friend.

I learned pretty quickly that there are two types of players who sign professional baseball contracts: prospects, and those who play catch with prospects. On any given Minor League team, especially at the lower levels at which I toiled, there are only a handful of real prospects — those players whom the organization believes will one day wear a big-league uniform. The rest are roster-fillers, players who help fill out the lineup so real games can be played.

I was a switch-hitting utility player reasonably adept at playing second base, third, and shortstop. In college, I had also become serviceable behind the plate, so there were four positions I could play without embarrassing myself too badly. As a hitter, my best years were behind me. I had no power, was an average runner, and having my throwing shoulder rebuilt the year before had robbed me of the only decent tool I once possessed.

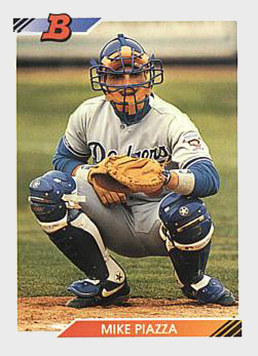

I played catch with Mike Piazza, who would go on to become arguably the best hitting catcher to ever play baseball, and was recently inducted into the Hall of Fame. Though I felt I could defend better than Mike, the difference in hitting was staggering: had we been artists, Mike would have painted the Sistine Chapel, while I rattle canned graffiti on highway overpasses.

Needless to say, Mike was a prospect; my job was to get him loose.

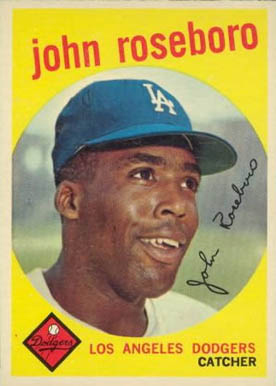

That year, I also met the legendary former Dodgers catcher John Roseboro, one of a handful of roving instructors paid by the Dodgers to visit all the minor league clubs in the organization to evaluate and work with the prospects for two or three days at a time. Others include Dave Walace, now pitching coach for the Orioles; “Sweet Lou” Johnson, whose battle with drugs once saw him use his World Series ring as collateral for cocaine, and who parlayed his successful rehabilitation into a meaningful role with the Dodgers, working with outfielders and speaking to players about avoiding the pitfalls of drugs and alcohol; and Dick McLoughlin, a salty, hard-drinking former Triple-A manager whose specialty was bunting, a skill he expected you to do with great accuracy. Once, during a drag bunting drill, Mac set his LA hat on the third base line. He then set my Salem hat on the grass four feet from the line before asking, “Where do you want your (expletive deleted) mail sent?”

Point taken.

ROSEBORO — ROSIE TO EVERYONE — CAUGHT FOR THE DODGERS from 1957 to 1967, was an All-Star six times, won three Gold Glove awards, and was a three-time World Series champion. A gifted storyteller, he sat us down under a maple tree and just talked to us — priceless stuff you can’t get anywhere, about disguising your signs when a runner is on second base, how to stay fresh over a long season, and what it was like to catch Koufax.

On Rosie’s final day with us, I finally got the nerve to ask him about the Giants, about Juan Marichal, and about one of the most notorious incidents in all of sports. In 1965, three months before I was born, the Dodgers faced the Giants’ best pitcher, Marichal, a fiery Dominican known for his pinpoint control and willingness to intimidate batters by throwing at their heads. To counter, the Dodgers sent out their ace, Sandy Koufax, the best pitcher in baseball and a calm gentleman.

“From the first pitch, Marichal was gunning for us,” said Rosie. “He threw at everyone. I told Sandy he needed to answer back. He agreed, but he wouldn’t do it — he just kept pitching away. I figured he must have been waiting for Marichal to come to the plate. But when he came up, and Sandy threw outside again…well, I figured it was time for me to take matters into my own hands. When I threw the ball back to the mound, I leaned over into the batter’s box a little and the ball passed close to Marichal’s face. The next pitch, I leaned a little further and my throw passed a little closer to his face. The third time, I leaned way over and my throw grazed his ear. He started jawing at me, and when I took my mask and helmet off and started to stand up, he hit me over the head with his bat — three times. I remember trying to look up, and then the blood just started pouring down my face. I don’t remember much after that.”

Marichal’s blows to Roseboro’s head started a huge brawl. Rosie was sent to the hospital; Marichal was suspended nine games and fined $1,750. After his return, Marichal lost his last three decisions, while the Dodgers won 15 of their last 16 games and the National League pennant, on their way to becoming World Series champions.

“Juan and I are pretty good friends today, believe it or not,” said Rosie, smiling.

AS A PLAYER YOU ARE OFTEN CONCERNED — sometimes overly so — with who respects you. I was small, skinny, and injured. I was not built like the other guys on the club, and didn’t get to play much. I spent most of my time in the bullpen, catching young pitchers with terrific arms and no idea where they were throwing the ball. If I hadn’t realized it sooner, it was becoming clear that I was not a prospect, and that the bullpen was the place my playing career would end. The manager never spoke to me. Most of the roving instructors walked right past me to work with the prospects they had been sent to see. And all of my passion, love for the game, and hard work was going unnoticed because it was wrapped in a package of limited skill. I was making $700 a month to catch in the bullpen and throw occasional batting practice. I got to play rarely, mainly in lopsided games at second base, third base, and behind the plate. I knew what they thought of me.

One July day when Rosie was in town, he stood next to me while I was waiting to enter the cage to take my batting practice swings. As the hitter before me completed his last round, Rosie put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Swing hard, son. Just in case you make contact.” I couldn’t tell if it was a jab or the best advice I had ever received, so I faked a smile and entered the cage.

The manager was throwing batting practice. As I stepped to the plate, I recognized the familiar body language that screamed his disdain for a player so utterly devoid of talent. I knew he preferred to spend his energy improving a prospect, rather than wasting his arm on a hack like me. Nevertheless, he reluctantly tossed pitches to the plate, which I peppered on lines into the outfield. It wasn’t that I had done poorly in my daily BP, but for some reason, that day, I got his attention. He even stopped, twice, to turn and watch balls sail over the left-field fence, which, for me, did not happen often. From behind the cage Rosie said, “Attaway, college boy. That’s how you do it. Tommy, how come we don’t get more guys to hit like this kid? We ought to get him in the lineup tonight.” It was arguably my best moment as a professional baseball player, and I prayed the manager had heard him.

He did not, and I spent the night catching in the bullpen.

In early September, the club fell short in its quest for the Northwest League championship, and guys prepared to head to Pennsylvania or Baton Rouge or Venezuela or the Dominican Republic, or wherever they called home. I stopped by a party following the last game, mainly to say goodbye to the few friends I had made. I wanted desperately to rejoin them, healthy, at spring training in Vero Beach in March, but I gathered from the way the season had gone that getting an invitation would be a long shot. After spending the season being thrashed in the bullpen by errant fastballs and fifty-five foot curves, and getting very few at-bats, the writing on the dugout wall was pretty clear. As I was leaving, Mike Piazza shook my hand and said, “See you in Vero.”

In early September, the club fell short in its quest for the Northwest League championship, and guys prepared to head to Pennsylvania or Baton Rouge or Venezuela or the Dominican Republic, or wherever they called home. I stopped by a party following the last game, mainly to say goodbye to the few friends I had made. I wanted desperately to rejoin them, healthy, at spring training in Vero Beach in March, but I gathered from the way the season had gone that getting an invitation would be a long shot. After spending the season being thrashed in the bullpen by errant fastballs and fifty-five foot curves, and getting very few at-bats, the writing on the dugout wall was pretty clear. As I was leaving, Mike Piazza shook my hand and said, “See you in Vero.”

That would be great, I thought.

I haven’t seen him since.

In time, my shoulder would make a full recovery. But the same calendar that measured my health could do nothing to change my unassailable mediocrity. Two months later, on a rainy November day, I responded to a notice summoning me to the local post office to collect a certified package. Inside was a letter from the Dodgers thanking me for my service to the organization and granting my unconditional release. My professional baseball career was over.

I paused for a long moment, as if someone would pull the paper from my fingers, just as Hank had done five months earlier when he offered me the contract. Alone in my car, with the wipers clearing rain from the windshield, I laid the letter in my lap and wept; my dream of playing in the big leagues was over. I was 23 years old.

IT IS A CRUEL GAME, BASEBALL. It permeates your skin and swims in your veins, makes you believe that it will reciprocate your love and loyalty, only to mire you with sadness and unrelenting failure. Much is said about the best hitters in the game, and how even they make outs 70% of the time. Less is said about the rest of us.

Years later, I realized that Hank had been right: I was never meant to be a big-league baseball player. He knew that instinctively the day he offered me a contract, then pulled it from my fingers. That day, instead of telling me what I wanted to hear, he told me what I needed to hear. Thanks to him, I didn’t wallow for the rest of my life, thinking I had been screwed out of a Major League playing career that I did not deserve. From the start, I was an outsider looking in. But thanks to Rosie, for one hour in July of 1989, I felt like the best player on a professional baseball team — a feeling I will savor and remember as long as I live.